This desperate clinging to tradition has earned iconography a bad rep amongst the rest of the artistic community. Us iconograhers are seen as stifling our personal views and clinging to a past that has no power to save. Not that I'm saying we need to earn the respect of secular artists; I'll take them more seriously once they stop idolizing brown squares and selling them for millions of dollars. But they do have a point. Why do we stay away from the obviously artistic sides of iconography and stay as mere copiers of what came before? The answer's a bit complicated and has everything to do with happened to us as an artistic community. It all started with the most profound and beautiful icon ever made: Rublev's Trinity.

The Hospitality of Abraham was a common piece in the iconographic world. It was the only time that the Holy Trinity was allowed to be painted, so it shows up a bit in iconographic history. Normally the icon shows Abraham and Sarah serving the three angels, who in Eastern thought are the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The scene's also got a bit more of a wide shot to it as well. Rublev cut all that out and just focused on the three angels, creating an entirely new icon. He felt something tug at him and created an icon that is so profound that not only has the Russian Church said that no other Trinity prototype shall ever be made but it's even been listed as proof for the existence of God! Rublev did not stick to iconographic tradition, but instead went with his gut and made an icon that spoke to him. His dialogue with God wound up on the board and we now have the most beautiful icon ever made. And it was an inspiration for others to try their hand at making icons that show Tradition but aren't straightjacketed by the past.

And then Peter the Great showed up, along with a period of Latinization. While I have the utmost respect for my Latin brethren there's a lot to be said for not crossing the streams; streams were crossed here, majorly. Latin and French were imported wholesale, and "icons" of God the Father (a theological impossibility!) became prominent. The Russian Church tried to stop the stream of Westernizations, particularly in their art, but they were so disconnected from the Fathers that they could only slap wrists, to no great avail. Icons were bastardized, becoming "Italianized" and looking like pretty European pictures with no spiritual depth. The next few centuries were ones of great decadence and straying from the heights achieved by Rublev and his master, Theophan the Greek. It wasn't until closer to the 20th century that iconography began to return to it's patristic roots.

When it's laid out like that it's very easy to understand why people are so for just copying the models of old: we've only just come out of a period of decadence. But going the opposite way doesn't help anything. The early icons worked because the iconographers were people of prayer who wrote/painted according to Tradition and their personal experience of God. If the room to personal innovation in respect for Tradition is removed then all that will be left is a lifeless art, devoid of any spiritual value. Copying is not enough. We must strive to express God as we see Him in Tradition.

|

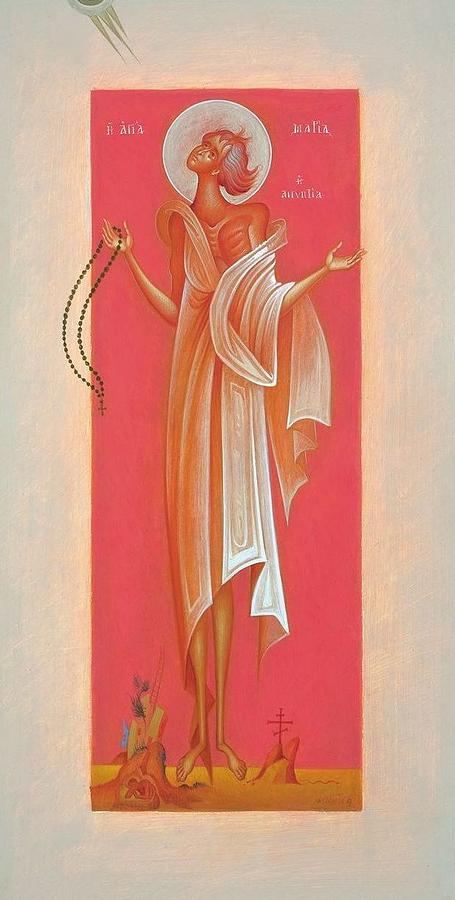

| St. Mary of Egypt, by the hand of George Kordis |

Sticking to iconographic tradition slavishly will not make a work more of the Spirit, that's being a Pharisee at it's finest. Traditions are not to be a straightjacket for the human spirit, but a fence alongside the edge of a cliff, keeping us safe so we can play on the playground that's inside the fence. Tradition is not a coffin, but a cast for broken bones and hearts. Growth to wholeness, to holiness, is not optional. The cast doesn't mend the bone. It just makes sure the bone grows right.

No comments:

Post a Comment